When you hear “Firebase,” you might think of hackathons, mobile app backends, or startup MVPs. It’s often typecast as a tool for rapid prototyping, a “lite” backend for developers who don’t want to manage servers.

From a professional cloud architect’s perspective, this view is dangerously incomplete.

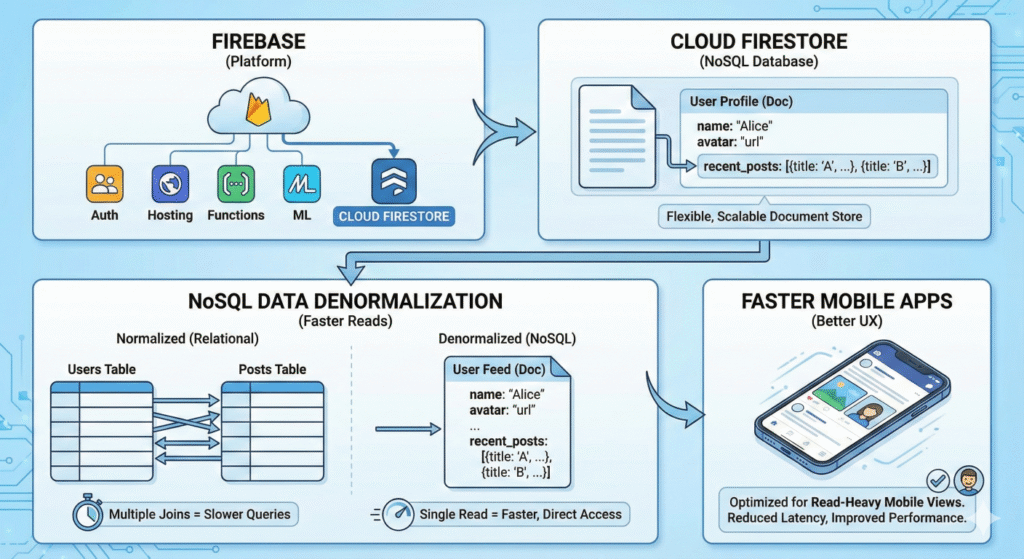

Firebase isn’t a “lite” tool, it’s a strategic abstraction layer. It’s a fully-managed, opinionated suite of services that runs on Google Cloud’s global infrastructure. It’s designed to solve a specific set of problems namely, client-side application development, real-time data synchronization, and serverless compute at massive scale.

This article isn’t a “how-to” for building your first app. It’s an architect’s guide to understanding where Firebase and its flagship database, Firestore, fit into an enterprise ecosystem, what trade-offs you’re making, and how to design systems that are secure, scalable, and cost-effective.

Deconstructing the Platform: Firebase is Not Just a Database

First, let’s clear up a common misconception. Firestore is a database. Firebase is the platform, a comprehensive suite of tools (a Backend-as-a-Service or BaaS) that includes:

- Databases: Cloud Firestore & Realtime Database

- Compute: Cloud Functions for Firebase (a FaaS wrapper for Google Cloud Functions)

- Identity: Firebase Authentication (managing user sign-in)

- Storage: Cloud Storage for Firebase (for user-generated files)

- Hosting: Firebase Hosting (a global CDN for static assets)

- Ops & Analytics: Crashlytics, Performance Monitoring, Google Analytics

As an architect, your first decision is not just “database,” but “platform.” When you adopt Firebase, you’re buying into a managed, event-driven ecosystem. The real power isn’t just using Firestore; it’s using Firestore to trigger a Cloud Function that processes an image saved to Cloud Storage, all authenticated by Firebase Auth.

The Core Database Decision: Firestore vs. Realtime Database

Firebase offers two NoSQL databases. Choosing the right one is a foundational architectural decision.

| Feature | Cloud Firestore | Realtime Database (RTDB) |

| Data Model | Document-Collection (hierarchical) | Single, large JSON tree |

| Querying | Rich, indexed, compound queries | Deep, path-based, limited filtering |

| Scalability | Massive, automatic multi-regional | Scales by sharding (more manual) |

| Offline Support | Excellent (Mobile/Web) | Good (Mobile) |

| Pricing Model | Per operation (read/write) & storage | Per storage & network bandwidth |

| Typical Use | Most new apps, complex data, global scale | Simple, high-frequency, low-latency needs |

The Architect’s Takeaway:

For 90% of new, complex applications, Cloud Firestore is the default choice. It’s designed for global scale, offers robust querying, and has a more structured data model.

The Realtime Database is a specialized tool. You’d choose it if your primary requirement is extremely high-frequency state-syncing (like a real-time collaborative editor or a game) and your data structure is very simple.

Architecting for Firestore: Embracing Denormalization

This is the most critical section. If you come from a relational (SQL) background, you must fundamentally shift your thinking. Treating Firestore like a SQL database is the number one cause of performance bottlenecks and runaway costs.

The Model: Collections and Documents

Firestore is a document-oriented database.

- Document: The basic unit of storage. It’s a set of key-value pairs, essentially a JSON object.

- Collection: A container for documents.

The key rule is that documents cannot contain other documents, but they can point to subcollections.

users (collection)

└── user_alice (document)

├── name: "Alice"

├── email: "alice@example.com"

└── orders (subcollection)

└── order_123 (document)

├── item: "SKU-456"

├── amount: 99.99

The Golden Rule: Design for Your Queries

In SQL, you design for data integrity (normalization). In Firestore, you design for your application’s access patterns (queries).

This means you must denormalize your data. If your app’s main page needs to show a user’s 5 most recent posts, you do not query the users collection and then query the posts collection. That’s two round trips and inefficient.

Instead, you would store a copy of that post data directly on the user document.

Relational (Bad) Approach:

/users/alice

/posts/post_abc (author: "alice")

/posts/post_xyz (author: "alice")

Query: Get user ‘alice’. Then, query ‘posts’ where author == ‘alice’.

Firestore (Good) Approach:

/users/alice

├── name: "Alice"

└── recent_posts: [

{ id: "post_xyz", title: "My new post" },

{ id: "post_abc", title: "Hello world" }

]

/posts/post_xyz

├── author_id: "alice"

├── author_name: "Alice" <-- DENORMALIZED

├── title: "My new post"

└── body: "..."

Query: Get user ‘alice’. All data is present.

Yes, this means data is duplicated. When “Alice” updates her name, you now have to update it in her user document and in every post she’s ever written. This is the central trade-off.

You are trading write-time complexity and storage for massive read-time performance and scalability.

How do you manage this duplication? With Cloud Functions, which we’ll cover in a moment.

Security by Design: The Firewall at the Data Layer

In a traditional architecture, your app server protects your database. In a serverless Firebase model, the client (web/mobile app) connects directly to the database.

This is terrifying, until you understand Firebase Security Rules.Security Rules are not an add-on, they are your primary security model. They are a set of non-negotiable rules that live on the server and are evaluated on every single read, write, or delete request.

They are your application’s “firewall,” “validator,” and “auth controller” all in one.

Pitfall: The “Test Mode” Trap

The biggest mistake is leaving the default test rules in place:

// DANGEROUS! DO NOT USE IN PRODUCTION!

rules_version = '2';

service cloud.firestore {

match /databases/{database}/documents {

match /{document=**} {

allow read, write: if true;

}

}

}

This exposes your entire database to the world.

A Professional Security Ruleset

A proper ruleset is granular and context-aware. It uses the request.auth object (provided by Firebase Auth) to identify the user.

JavaScript

// A secure, production-ready example

rules_version = '2';

service cloud.firestore {

match /databases/{database}/documents {

// Users can only read/write their own profile

match /users/{userId} {

allow read, update, delete: if request.auth.uid == userId;

allow create: if request.auth.uid != null; // Any signed-in user can create a profile

}

// Anyone can read a post, but only the author can write it

match /posts/{postId} {

allow read: if true;

allow create, update, delete: if request.auth.uid == resource.data.author_id;

}

}

}

In this model, security is enforced at the data layer, regardless of what your client-side code tries to do.

What is Normalization & De-Normalization ?

Think of a database like a digital filing cabinet.

Normalization is like organizing your files perfectly. You separate every topic into its own folder so nothing is duplicated. It is neat, tidy, and efficient for saving data.

Denormalization is like photocopying documents and stuffing them into multiple folders. It is messy and uses more space, but it makes reading faster because you don’t have to run between different cabinets to find related papers.

The Integration Layer: Cloud Functions

So, how do you handle that data denormalization we talked about? Or send a welcome email? Or run a credit card payment? You can’t do that on the client. The answer is Cloud Functions for Firebase.

These are event-driven, serverless functions. You write small snippets of Node.js, Python, or Go code that respond to “triggers” in your Firebase ecosystem.

The Architect’s Use Cases:

- Data Integrity: A user updates their name? An

Updatetrigger on their user document can start a function that updates all their posts. - Data Sanitization: A user creates a post? An

Createtrigger can scan the text for inappropriate language before it’s saved. - System Integration: A new order is written to the

orderscollection? AnCreatetrigger can call the Stripe API, send an email, and write to a BigQuery analytics log.

Code Snippet: A Denormalization Trigger

Here is a function that solves our earlier problem. When a user updates their name in their /users/{userId} document, this function finds all posts by that user and updates the author_name.

JavaScript

// index.js (Node.js)

const functions = require('firebase-functions');

const admin = require('firebase-admin');

admin.initializeApp();

const db = admin.firestore();

exports.updateAuthorName = functions.firestore

.document('users/{userId}')

.onUpdate(async (change, context) => {

const newValue = change.after.data();

const previousValue = change.before.data();

const userId = context.params.userId;

// If the name didn't change, do nothing.

if (newValue.name == previousValue.name) {

return null;

}

console.log(`User ${userId} name changed. Fanning out update...`);

// 1. Find all posts by this user

const postsRef = db.collection('posts').where('author_id', '==', userId);

const snapshot = await postsRef.get();

// 2. Batch update all of them

const batch = db.batch();

snapshot.forEach(doc => {

batch.update(doc.ref, { author_name: newValue.name });

});

// 3. Commit the batch

return batch.commit();

});

This is the serverless architectural pattern. Logic is broken into small, event-driven pieces that react to state changes in the database.

The Catch: Cost and Performance

Firebase isn’t a silver bullet. Its scalability comes with a very specific cost model that you must design for.

You are billed primarily on:

- Number of Reads

- Number of Writes

- Number of Deletes

- Data Storage

- Network Egress

You are not billed on CPU or RAM. This means a poorly designed query can cost you thousands of dollars, even if it returns one document.

Example: The N+1 Query Pitfall

Imagine you want to show a list of 100 friends.

- Bad Query: You fetch a list of 100 friend IDs. Then, you loop through that list and fetch each friend’s document one by one.

- Cost: 1 read (for the list) + 100 reads (for the documents) = 101 reads.

- Good Query: You use an

inoperator to fetch them all at once. - Cost:

db.collection('users').where('user_id', 'in', friendIdList).get()= 10 reads (Firestore’sinoperator is billed as 1 read per 10 items in the list). - Best Query: You denormalized and stored the friend’s names on the user document.

- Cost: 1 read.

Performance and cost are two sides of the same coin in Firestore. Every design decision must be weighed against its impact on read/write operations.

Command Reference: The Architect’s Toolkit

As an architect, you’ll spend less time in the console and more time with infrastructure-as-code and the CLI. These are the commands you’ll use most.

| Command | Description |

firebase init | Initializes a new Firebase project (Firestore, Functions, Hosting). |

firebase deploy | Deploys all assets (Rules, Functions, and static files) to production. |

firebase deploy --only firestore:rules | Deploys only your security rules. (Use this in CI/CD). |

firebase deploy --only functions | Deploys only your Cloud Functions. |

firebase emulators:start | CRITICAL. Starts a local emulator suite. |

firebase projects:list | Lists all Firebase projects your account can access. |

The Firebase Emulator Suite is non-negotiable for a professional team. It allows you to run a local version of Firestore, Auth, and Functions on your machine. This means you can test your security rules and function triggers without incurring cloud costs or polluting your dev environment.

Final Verdict: An Architect’s Assessment

Firebase and Firestore are a high-level abstraction for Google’s globe-spanning infrastructure, optimized for a specific, modern application pattern: client-driven, real-time, and event-driven.

Use Firebase when:

- Your project is client-heavy (web, mobile).

- You need real-time data sync.

- You want to minimize server management and DevOps overhead.

- Your access patterns are well-defined.

- You are building an event-driven, serverless architecture.

Be cautious when:

- Your application requires complex, relational queries, and ad-hoc analytics (a SQL database is better).

- You have a “write-heavy, read-light” workload (the cost model may be unfavorable).

- Your team is unwilling to learn NoSQL data modeling patterns.

Adopting Firebase is an architectural commitment. You are trading the fine-grained control of IaaS (like Compute Engine) for the velocity and managed scale of BaaS/FaaS. For the right project, it’s not just a shortcut; it’s a powerful and strategic advantage.